Smugglers. “Criminals”. They were scholars, teachers, avid readers. They loved their country more than anything and they wanted to be Lithuanians. They became book smugglers to protect their identity, their traditions and the soul of Lithuania. They were the knygnešiai, the book carriers.

From 1864 to 1904 they tried to keep the Lithuanian language alive, despite the efforts of the Czar who wanted to erase it. Because to conquer a nation, you have to erase its language, its traditions, you have to prevent the language from being used and taught in schools.

Every year, on May 7th, Lithuania celebrates the end of the Czarist ban that forbade the publishing and distribution of books in Lithuanian: it is the Lithuanian Press Restoration, Language and Book Day.

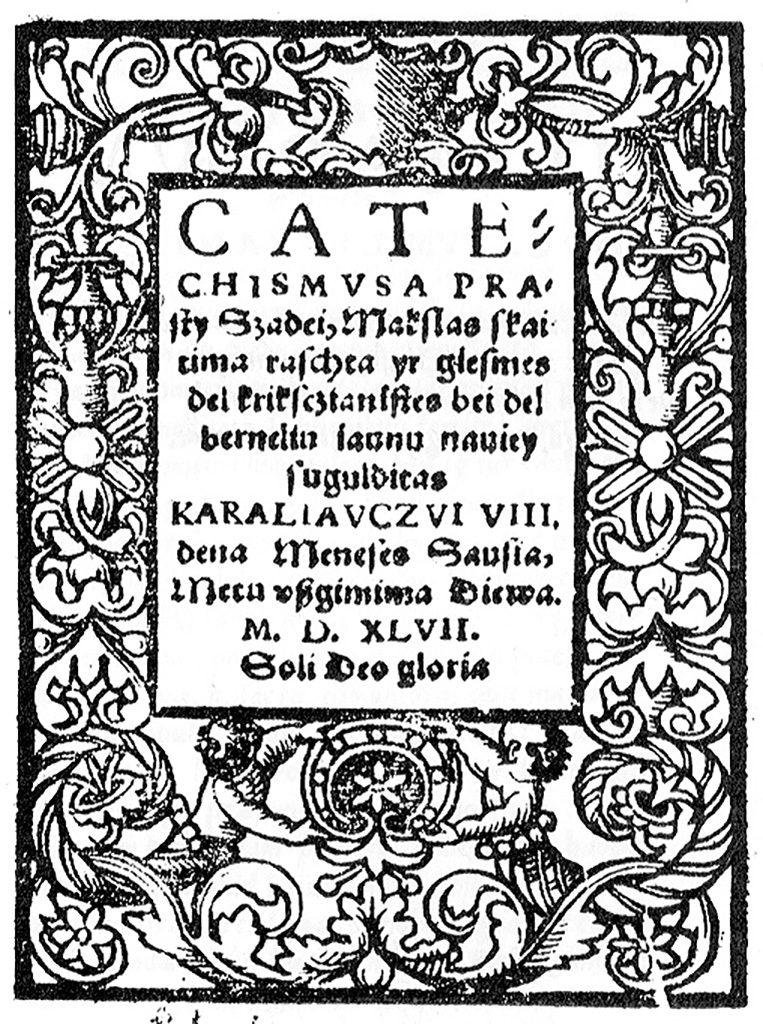

Lithuanian is an ancient language. Many scholars believe it is one of the oldest still alive today. It belongs to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European languages and it still shows some influences from Sanskrit.

In its long history the use of the Lithuanian language was forbidden many times, but today it is very much alive thanks to the efforts and the bravery of the people who secretly kept on publishing books and newspapers. Many history books were hidden during the bleakest times of the country’s past. From the Czars to the Nazi and the Soviet eras. All of them brutal regimes whose goal was to erase the Lithuanian identity.

During the Czarist times, the country underwent a policy of russification that forbade people from using the Lithuanian language. In those years, the resistance against the disappearance of the language was very strong. Books were printed abroad and smuggled into the country thanks to citizens who emigrated to Europe and to the US. The help of the Catholic church was essential, too.

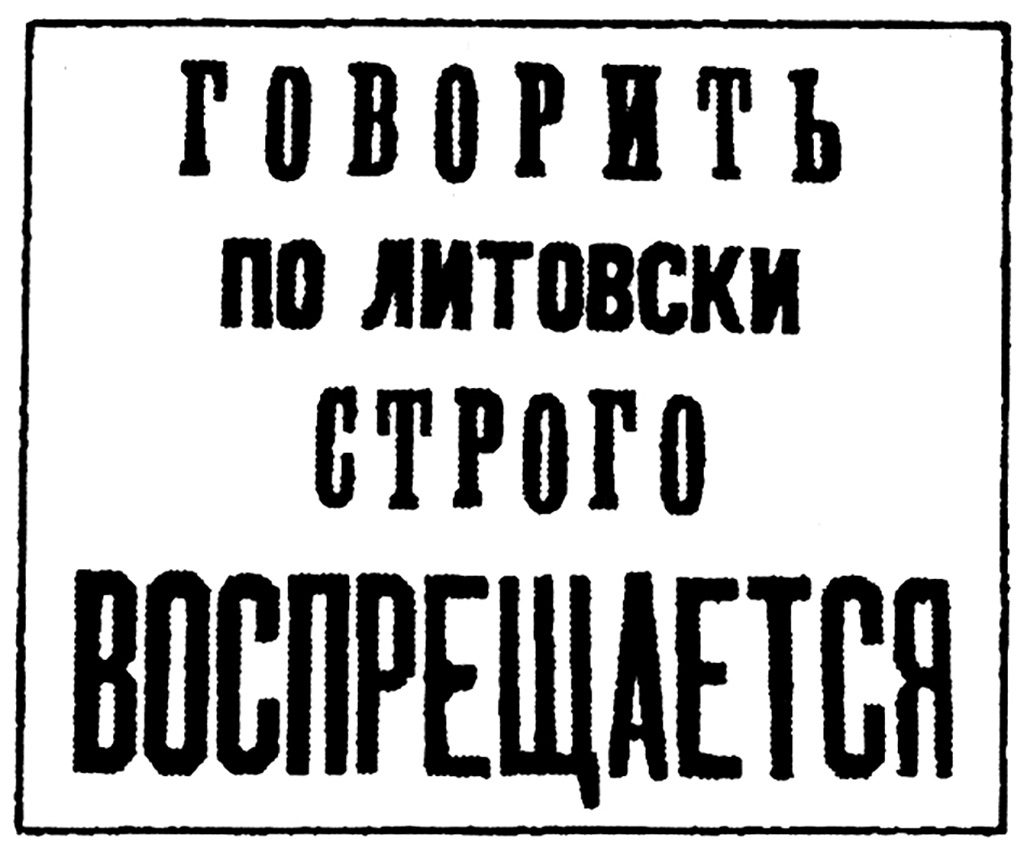

The Russian ban was put into place in 1864. The riots in the latter half of the 19th century – all of them brutally suppressed – induced another government crackdown. The use of the Lithuanian language was completely prohibited along with the Latin alphabet. They introduced the Cyrillic script. The Catholic church was prevented from printing prayer books in Lithuanian, while in schools and universities it became mandatory to study Russian and to use the Cyrillic script.

Lithuanians weren’t going to give up so easily: they kept on secretly printing books in their own national language. The Knygnešyst movement was born. Unique to Lithuania, the word means “book smuggling”; it was carried out by knygnešiai, or book smugglers. To the Czars, they were criminals who had to be punished. The books were published abroad, particularly in the territories of then-Eastern Prussia and then smuggled into the country.

Those who engaged in those activities risked death by firing squad. If they were lucky, they would be sent to Siberia instead.

Despite the ban and thanks to the book smuggling, the Lithuanian language flourished. Hidden from sight, in the countryside, many “daraktoriai” taught to write and speak Lithuanian in makeshift schools. The knygnešiai movement was very important for the whole country, especially in the countryside.

The Czar lifted the ban in 1904. It hadn’t worked. The Lithuanian language was still alive. A year later, the first Lithuanian bookstore was officially inaugurated in Panevėžys, in the Eastern part of the country. It was Juozas Masiulis who founded it, a proactive man who loved to read, loved Lithuania and had been a knygnešiai. The bookstore had a pivotal role in the dissemination of the Lithuanian culture and traditions. During the republican times (1918-1940) it maintained good relationships with bookstores and libraries abroad.

In the Interwar period, between 1918 and 1940, Lithuania was an independent country. With the Nazi and the Soviet occupations the country lived one of its bleakest times: the Holocaust almost completely obliterated the Jewish community, around 250.000 people; the deportations in Siberia by the Soviets condemned hundreds of thousands of people and then there was armed resistance against the Soviet army until 1953.

The opposition to the Soviet regime, albeit not armed and in other forms, continued until the independence in 1990.

The cultural “cleansing”

The Soviets weren’t much better than the Czars: they tried in any way possible to limit the printing of books and magazines in Lithuanian. Erasing the national identity, that’s the first step of any totalitarian regime. In schools, teaching Russian became mandatory and many books, also those of great historical value, were burned or became unavailable.

The National Public Library of Lithuania, today at the end of Gedimino Prospektas in Vilnius, next to the Parliament, was built in 1919. The building has a troubled history which mirrors the history of its home country. In the first few years since its founding it became part of a wide cultural ecosystem which comprised universities and bookstores abroad. It acquired many books and from 1919 to 1921 a public reading room was opened.

When the Soviets came, the Library changed. Books in Lithuanian disappeared, the shelves were stocked with books in Russian. The goal was clear: destroying culture and traditions, as well as preventing any contact with libraries and bookstores that were not part of the USSR. In 1941, the Germans came. The rooms of the National Library were occupied by soldiers and almost all operations ceased. For a short period of time, at the end of the war and under Soviet rule, the building was closed and all the books were moved to the Chamber of Commerce.

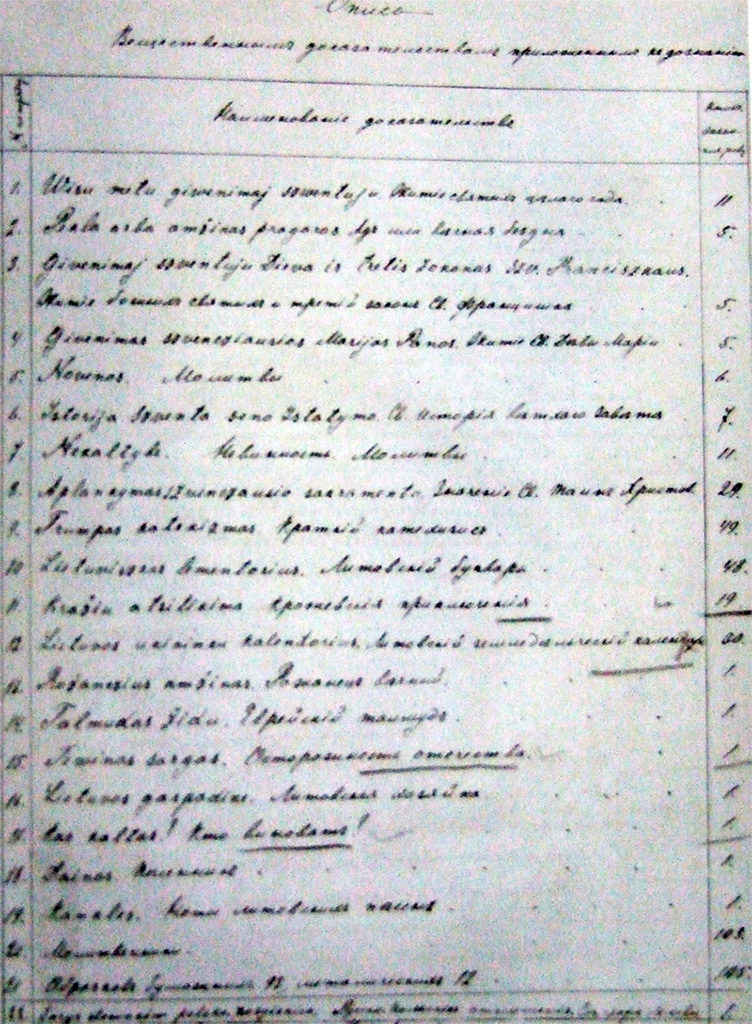

The cultural “cleansing” was just beginning. The Soviets were raging an ideological battle against anything connected to the history of Lithuania, forcing schools to speak Russian and banning books in Lithuanian, deemed dangerous and anti-Soviet. Many books and papers were removed from the library catalogue, hidden or burned. A few books were available only to those who could show a special permit released by the security services. That permit was of course denied to the average citizen.

“Lietuva, Tėvyne mūsų,

Tu didvyrių žeme,

Iš praeities Tavo sūnūs

Te stiprybę semia”

These are the first lines of the Lithuanian national anthem:

Lithuania, our dear homeland,

Land of worthy heroes!

May your sons draw strength

From your past experiences.

The Soviets, just like the Czars before them, weren’t successful in their efforts to erase the national identity. Lithuania had always been a thorn in the side of the USSR leaders. It was the first country to gain freedom from the galaxy of the Soviet empire (Translation by Inglese Americano)

Pingback: Death by Shooting Squad for Using One’s Mother Tongue: An Incredible Story of the Lithuanian Language under Czars and Soviets – Andrew Andersen

Thank you!

The history of the book smugglers in Lithuania is told in an historical novel available on Amazon “The Last Book Smuggler” by Birute Putrius .

Beautiful stories the faith and fight to preserving your heritage and cultural language.